The story of a WWII sailorstuck in the South Pacific

On Dec. 7, 1941, Harlan Shirey “Bud” Yenne Jr. was struggling for good grades at an exclusive boarding school for boys in western Pennsylvania.

The destroyer-tender USS Prairie was stationed at Argentia (Newfoundland), tending Allied ships in the Atlantic.

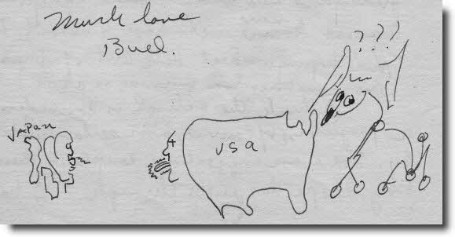

In the aftermath of the surprise attack by the Empire of Japan, 16-year-old Bud wrote to his parents in Cleveland: “Those Japs wouldn’t stand a chance against us Kiski boys.” A frequent doodler, the high school sophomore drew an editorial cartoon at the end of the letter showing Japan and the United States exchanging Bronx cheers across the Pacific.

It wasn't long before he was right in the middle of it.

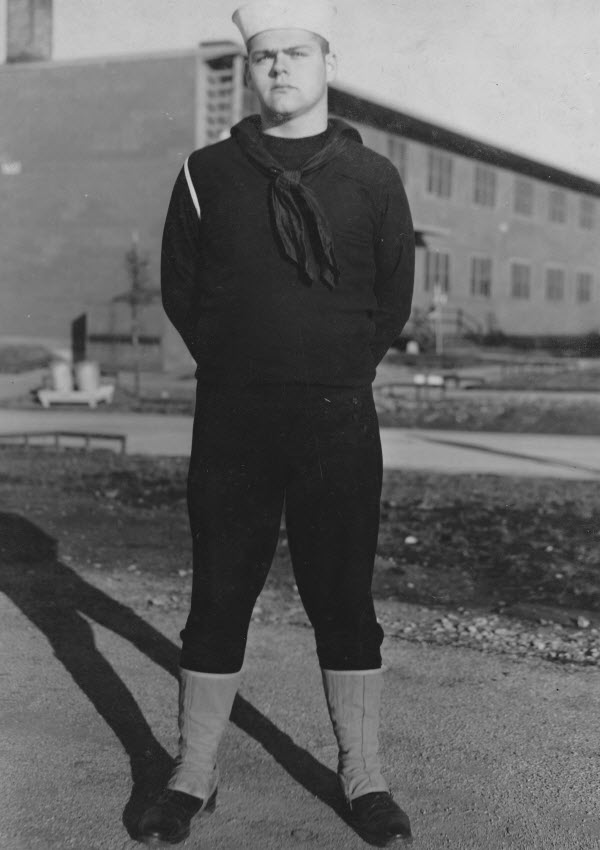

Bud enlisted in the Navy in the summer of '43 after high school graduation at age 18. He had applied to the Navy's V-12 College Training Program, but poor vision had disqualified him. Ironically, he shot a rifle for the first time in boot camp and hit the target three out of his first four tries. He played cornet in the drum and bugle corps at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago and eventually became regimental bugler.

By late Fall of ‘43, the USS Prairie had moved to Pearl Harbor from the cold waters of the Atlantic to support advancing forces of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The Navy, meanwhile, had moved Bud to the University of Chicago for training in radio communications. And by the new year, he was on his way to the Dixie class destroyer tender serving ComServRon 10, a service squadron of tankers, oilers, refrigerator ships, ammunition ships, supply ships, repair ships and the like.

.gif?timestamp=1320089288702) He spent much of his naval service in secret locations. "Loose lips might sink ships" was the famous warning, and letters were monitored closely by Navy censors. Once his family sent him a scarf for warmth, which got a laugh from his shipmates because they were suffering from the tropical heat in the South Pacific -- first in Majuro, then Eniwetok, but mostly in the atoll of Ulithi. Described as “the atoll on the edge of hell” by one historian, Ulithi became a massive floating service station for the combat ships of major naval engagements like the Battle of Leyte Gulf. But few Americans ever heard of it -- even after the war.

He spent much of his naval service in secret locations. "Loose lips might sink ships" was the famous warning, and letters were monitored closely by Navy censors. Once his family sent him a scarf for warmth, which got a laugh from his shipmates because they were suffering from the tropical heat in the South Pacific -- first in Majuro, then Eniwetok, but mostly in the atoll of Ulithi. Described as “the atoll on the edge of hell” by one historian, Ulithi became a massive floating service station for the combat ships of major naval engagements like the Battle of Leyte Gulf. But few Americans ever heard of it -- even after the war.The USS Prairie eventually ended up in Tokyo Bay for the occupation of Japan, and its sailors were issued Japanese army rifles as souvenirs. For Bud, who often wrote about the inglorious nature of his support role, the rifle might have served as a memento of his boot camp glory days on the shooting range. But for others, it might have addressed that empty feeling Ernie Pyle once wrote about: "One of the paradoxes of war is that those in the rear -- no matter what their battle experience -- want to get up into the fight, while those in the lines want to get out."

Bud wrote about that paradox, longed for home and contemplated his past and future in his letters. He came of age during his war duty, and that is most obvious as the care-free doodling vanished from his letters in 1945.

Recently found among my aunt's things in Cleveland, the letters posted here had been packed away unread for more than 65 years. They are arranged by years of service -- from training camp in 1943 to Bud's discharge in 1946 -- with timelines and notes supplied for perspective. -- John Yenne, November 2011

The destroyer-tender USS Prairie was stationed at Argentia (Newfoundland), tending Allied ships in the Atlantic.

In the aftermath of the surprise attack by the Empire of Japan, 16-year-old Bud wrote to his parents in Cleveland: “Those Japs wouldn’t stand a chance against us Kiski boys.” A frequent doodler, the high school sophomore drew an editorial cartoon at the end of the letter showing Japan and the United States exchanging Bronx cheers across the Pacific.

By late Fall of ‘43, the USS Prairie had moved to Pearl Harbor from the cold waters of the Atlantic to support advancing forces of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The Navy, meanwhile, had moved Bud to the University of Chicago for training in radio communications. And by the new year, he was on his way to the Dixie class destroyer tender serving ComServRon 10, a service squadron of tankers, oilers, refrigerator ships, ammunition ships, supply ships, repair ships and the like.

.gif?timestamp=1320089288702) He spent much of his naval service in secret locations. "Loose lips might sink ships" was the famous warning, and letters were monitored closely by Navy censors. Once his family sent him a scarf for warmth, which got a laugh from his shipmates because they were suffering from the tropical heat in the South Pacific -- first in Majuro, then Eniwetok, but mostly in the atoll of Ulithi. Described as “the atoll on the edge of hell” by one historian, Ulithi became a massive floating service station for the combat ships of major naval engagements like the Battle of Leyte Gulf. But few Americans ever heard of it -- even after the war.

He spent much of his naval service in secret locations. "Loose lips might sink ships" was the famous warning, and letters were monitored closely by Navy censors. Once his family sent him a scarf for warmth, which got a laugh from his shipmates because they were suffering from the tropical heat in the South Pacific -- first in Majuro, then Eniwetok, but mostly in the atoll of Ulithi. Described as “the atoll on the edge of hell” by one historian, Ulithi became a massive floating service station for the combat ships of major naval engagements like the Battle of Leyte Gulf. But few Americans ever heard of it -- even after the war.The USS Prairie eventually ended up in Tokyo Bay for the occupation of Japan, and its sailors were issued Japanese army rifles as souvenirs. For Bud, who often wrote about the inglorious nature of his support role, the rifle might have served as a memento of his boot camp glory days on the shooting range. But for others, it might have addressed that empty feeling Ernie Pyle once wrote about: "One of the paradoxes of war is that those in the rear -- no matter what their battle experience -- want to get up into the fight, while those in the lines want to get out."

Eighteen-year-old Harlan Shirey (Bud) Yenne Jr. at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center near Chicago in 1943.

Bud doodled a lot in his early letters. His trademark was the family dog. In this letter from school after the attack on Pearl Harbor, he drew a Bronx cheer at Japan.